Twenty-first-century art has gone “meta”: be it on the canvas, on the big screen or in literature, contemporary narratives are bursting with framing devices, fourth-wall-breaks and stories that admit their fictional status, or try a little too hard to deny it. How does our understanding of a story change when the story itself asks us to challenge the premises it was built upon? How do such ‘meta-stories’ reshape our views of the genres and representational legacies associated with them? Katrijn Van den Bossche addresses these questions in her PhD research, in the context of the FWO junior research project “Self-Reflexivity and Generic Change in 21st Century Black British Women’s Literature” (supervised by Janine Hauthal and Elisabeth Bekers). While the aesthetic innovation in Black women’s literature remained underappreciated during the postmodern period and well into the early 2000s, formal experimentalism by writers with non-hegemonic positionalities is increasingly acknowledged today. Postmillennial artworks often position themselves first and foremost as a constructed entity and call upon the audience to interpret art self-consciously, with a careful awareness of the specific artistic medium, the genre(s) the artwork draws on and the context that surrounds both the artwork and the audience in the process of cultural production. In this way, self-reflexive strategies and metadevices mediate the audience’s political engagement with the work and function as a catalyst for the development of (new) genres.

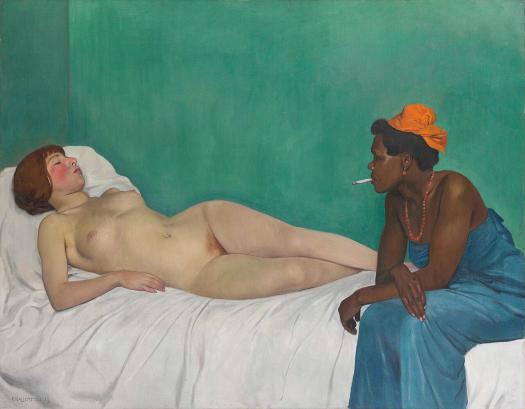

In a similar vein, the Bozar exhibition 'When We See Us' features many postmillennial artworks in which figures look back at the spectator or at their mirrored selves through a direct gaze. Examples of this can be found in the works Ying and Yang, Homage, The Birthday Party, Sundials and Sonnets, View of Yoei William, Two Reclining Women, 11pm Friday, John Mensah, Ibhungane 16 & 17, Marie Antoinette (Zora Neale Hurston portrait) and We Forgot How Life’s Supposed to Be. In the case of Roméo Mivekannin’s Le modèle noir d’après Félix Valloton (2019), the innovative use of this direct audience address self-consciously comments on the painting La Blanche et la Noire by Félix Valloton (1913). Valloton’s figural composition was inspired by Manet’s Olympia (1863) and Ingres' Odalisque à l'esclave (1839) and has been ambiguously interpreted as depicting sapphic desire and the racialized power-dynamic between mistress and maid. Mivekannin’s work adds to this interpretative tension by demonstrating a heightened awareness of the spectator’s gaze and foregrounding the figure of the ‘modèle noir’ in contrast to the impersonal sketch-like figure, who almost blends in with the pale bedsheet. Through the self-reflexive gaze both towards the spectator and this figural legacy, Mivekannin’s postmillennial iteration of this composition urges audiences to reflect on the historically marginal representation of Black women’s subjectitivity in the genre of portraiture, as well as on the role of the audience in experimental contemporary art. In doing so, this artwork allows us to interpret the racialized pictorial legacy it comments on anew.

Jean-Auguste-Dominisue Ingres, Odalisque à l'esclave, 1839, Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Bequest of Grenville L. Winthrop.

Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863, Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

Félix Vallotton, La Blanche et La Noire, 1913, Hahnloser/Jaeggli Stiftung, Zürich. Fine Art Images/ARTOTHEK.